Today, I received a message from my father: my grandmother—my son’s great-grandmother—has passed away.

She lived in China, far from where we are now. My son barely had the chance to meet her. The distance, the pandemic, and the passing of time meant their connection remained mostly in stories I told him. There are no photos of them together. No shared memories. And yet, she was a thread in the fabric of our family—part of where we come from.

When I heard the news, I stood still for a moment, then kept going—putting away laundry, finishing work, thinking about what to cook for dinner. But inside, I was flooded. Not just with sadness, but with something more tangled: memory.

As a child, I remember always wanting her attention. I would follow her around the house, try to sit near her, speak up just a little louder so she’d notice. But her days were filled with endless tasks—cooking, cleaning, taking care of others. Her affection wasn’t loud or obvious. I sometimes wondered if she saw me at all. But now, as an adult, and as a mother, I understand: she was showing love the way she could—with hard work, with presence, with sacrifice.

Still, that little girl in me who yearned for her gaze hasn’t gone away. And today, she’s grieving too.

Now, I find myself in the strange position of being the bridge between generations. Of holding my own grief quietly while also deciding how to explain it to my child. Should I tell him? Will he understand what it means to lose someone he barely knew?

In Chinese culture, children are often spared the details of death. Grief is something carried by adults, inwardly. We don’t cry in front of kids. We bow, we light incense, we keep going.

Here in Europe, it’s different. Parents talk openly about loss, even with young children. They read books about death, create rituals, light candles, and speak honestly—though gently—about what it means when someone is gone. It’s not easier, but it feels more human.

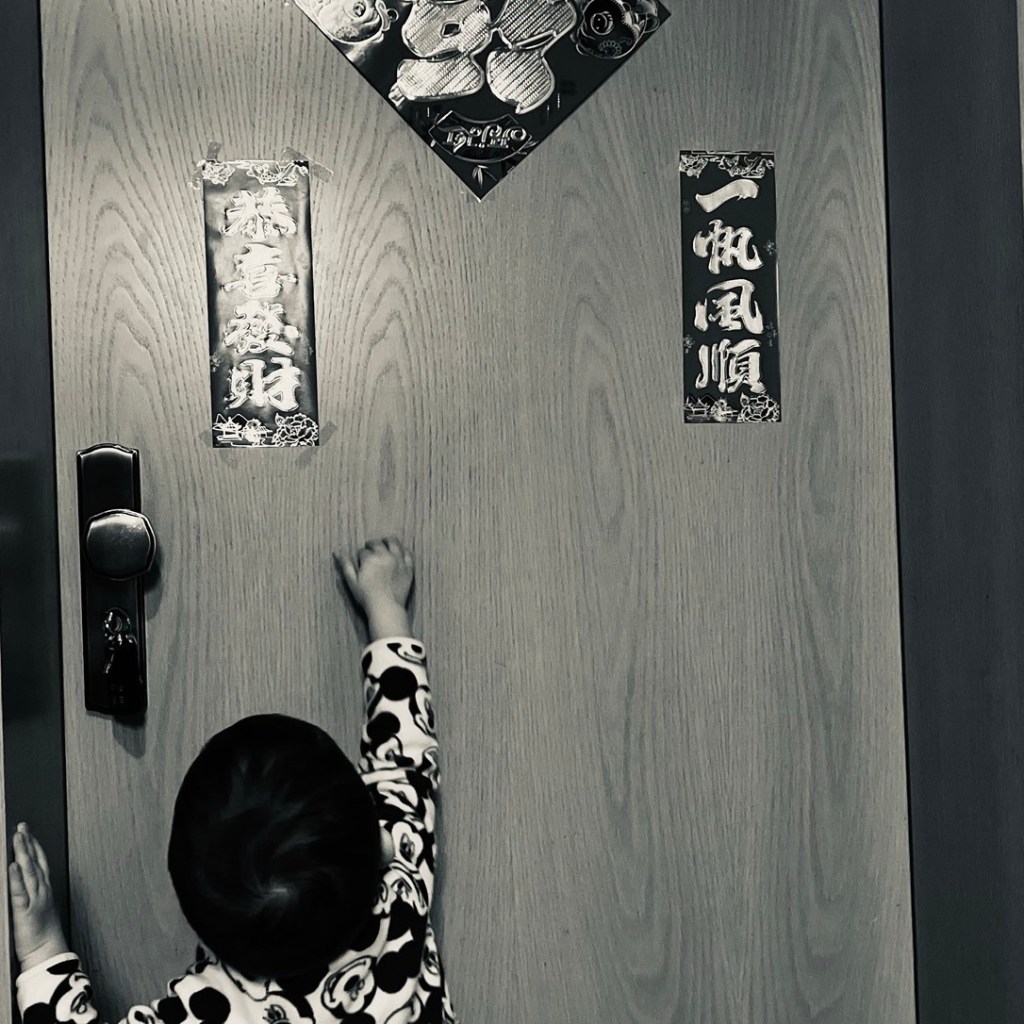

So, standing between these two cultures, I told my son the truth. I said his great-grandma died today. That she was very old, and very loved. That even though they didn’t know each other well, she is a part of him. He listened. He asked a few simple questions. And then he went back to play.

But I didn’t move on so quickly. I sat with the weight of everything: of not being there, of not saying goodbye, of remembering the quiet woman I used to follow around the house, hoping for a moment of her attention.

International parenting is full of these in-between places—where love, memory, and grief stretch across oceans and languages. I still feel lost. I miss being able to mourn with my family, to light incense with them, to hear their stories and share my own.

But maybe it’s enough that my son knows he comes from her. That a woman who never got to hold him still shaped his life, through me. And maybe the small, quiet sadness I carry today is a way of honoring her—the love she didn’t have time to show in words, but gave in her own way, every single day.

两种文化之间:告诉儿子太祖母去世的那一刻

今天,我收到了爸爸的消息:我的奶奶——我儿子的太祖母——去世了。

她住在中国,离我们很远。因为疫情、因为距离、因为生活节奏的变化,我的儿子几乎没有机会真正认识她。他们没有合照,没有共同的回忆。他对她的印象,只来自我偶尔讲起的只言片语。但她依然是我们家庭里重要的一环,是我们故事中的一部分。

得知消息时,我愣住了一会儿,然后继续做着手头的事——收拾衣物、完成工作、想着晚饭做什么。但我的心里却翻涌不止,那不是单纯的悲伤,而是一种更复杂的情绪——记忆涌上来。

小时候,我总是渴望奶奶的关注。我会跟在她身后,看她做家务,想办法靠近她,希望她能看我一眼,和我说说话。但她每天都忙得团团转,煮饭、打扫、照顾一家人。她的爱并不外露、不热烈,甚至不容易被孩子察觉。我曾经怀疑她是否在意过我。但现在,作为一个母亲,我终于明白:她只是用她能表达的方式去爱,用劳作来守护晚辈。

然而,那个小时候渴望被她看到的小女孩,还住在我心里。今天,她也在默默地哭泣。

现在的我,成了代际之间的桥梁。一边要压下自己的悲伤,一边还要思考要不要告诉儿子、该怎么告诉他。告诉他一个他几乎不认识的人去世了,他会明白吗?

在中国文化中,死亡常常是对孩子避而不谈的话题。我们习惯把悲伤留在心里,大人默默承担,不在孩子面前流泪。我们烧香、鞠躬,然后继续生活。

但在欧洲,方式很不同。父母会主动和孩子谈论死亡,用温柔但诚实的语言告诉他们有人离开了。他们读关于生死的绘本,点蜡烛、做告别仪式,让孩子也参与其中。这不容易,但很真诚。

于是,我夹在这两种文化之间,做出了选择。我告诉了儿子:今天,他的太祖母去世了。她年纪很大了,我们都很爱她。虽然他们不熟悉,但她是我们家的一部分,是他生命的一部分。他认真地听了,问了几个简单的问题,然后又去玩耍了。

但我没有那么快走出来。我坐在一旁,默默回忆着那个小时候的自己,想起那个总是默默做事的奶奶,那个我曾经努力想要靠近却总感到有些遥远的她。

跨文化养育的过程,就是充满这些夹缝时刻——我们把爱、回忆与悲伤拉长到两个世界之间、两个文化之间。此刻的我,依旧感到迷失。我想念和家人一起哀悼的机会,想念一起烧香、一起说故事的场景,想念那个我再也见不到的她。

但也许,能让我的儿子知道血脉深处的来处,便足够了。即便他从未被她拥入怀中,甚至不曾听懂她说的方言,那些揉进面粉里的牵挂、缝在棉被里的守候,早已通过我的眼睛住进了他的生命。此刻静默的哀伤,恰似当年她晾在阳台的旧围裙——沾着经年的油烟,却飘荡着最质朴的牵挂。

“阿嬷,愿您在天国安好无忧。您用一辈子在灶台前写下的家,如今我读懂了。您教我的那句’吃饭皇帝大’,我会用德语再说给曾孙听。那些没来得及说的家常,就托鼓浪屿的晚风捎去罢。”

Leave a comment